After listening to yesterday’s (Day 60) compositions from Falla and Berlioz, today’s album is a breath of fresh air.

And I’ve never been one of Haydn’s biggest fans.

But this is filet mignon compared to yesterday’s Big Macs.

Not that there’s anything wrong with Big Macs.

Sometimes – especially when one is in the car, barrelling down the highway at 70 mph – a filet mignon just won’t do.

In other words, there’s a time and a place for certain types of food, just as there’s a time and a place for certain kinds of music.

Yesterday’s compositions were operas. And they were extremely good. But that genre of music has never been a favorite of mine; hence, my comparison to Big Macs. There are times when I crave a Big Mac, and am thrilled to bite into one that’s been made well. Ditto for yesterday’s operas. They were tasty.

I remember when I listened to everything Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) composed. I was underwhelmed. And, by the second movement of his “Clocks” symphony (No. 101 in D) I remember why. If anything ever sounded like the ticking of a clock it’s Movement II (“Andante”) of Symphony No. 101 in D. It’s so metronome-like that I feel like dozing off.

There’s a time and a place for dozing off.

This isn’t it.

Face planting in my Asiago bagel (toasted twice!) with plain cream cheese would make me look silly.

Before I get to far afield with my comparisons between fast food and choice cow parts, I’d better get back to why I’m here.

The Objective Stuff

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Franz Joseph Haydn (1732 1809) was an Austrian composer of the Classical period. He was instrumental in the development of chamber music such as the piano trio. His contributions to musical form have earned him the epithets “Father of the Symphony” and “Father of the String Quartet”.

Haydn spent much of his career as a court musician for the wealthy Esterházy family at their Eszterháza Castle. Until the later part of his life, this isolated him from other composers and trends in music so that he was, as he put it, “forced to become original”. Yet his music circulated widely, and for much of his career he was the most celebrated composer in Europe.

He was a friend and mentor of Mozart, a tutor of Beethoven, and the older brother of composer Michael Haydn.

From it’s entry on Wikipedia,

The Symphony No. 101 in D major (Hoboken 1/101) is the ninth of the twelve London symphonies written by Joseph Haydn. It is popularly known as The Clock because of the “ticking” rhythm throughout the second movement.

Haydn completed the symphony in 1793 or 1794. He wrote it for the second of his two visits to London. Having heard one of his symphonies played in London with an orchestra of 300-strong, his Clock Symphony has that large scale grandeur written in it. On 3 March 1794, the work was premiered with an orchestra of 60 personally gathered by Haydn’s colleague and friend Johann Peter Salomon, who also acted as concertmaster, in the Hanover Square Rooms, as part of a concert series featuring Haydn’s work organized by Salomon; a second performance took place a week later.

As was generally true for the London symphonies, the response of the audience was very enthusiastic. The Oracle reported that “the connoisseurs admit [it] to be his best work.” Additionally, the Morning Chronicle reported:

As usual the most delicious part of the entertainment was a new grand Overture [that is, symphony] by HAYDN; the inexhaustible, the wonderful, the sublime HAYDN! The first two movements were encored; and the character that pervaded the whole composition was heartfelt joy. Every new Overture he writes, we fear, till it is heard, he can only repeat himself; and we are every time mistaken.

The work has always been popular and continues to appear frequently on concert programs and in recordings. An average performance lasts about 27 minutes.

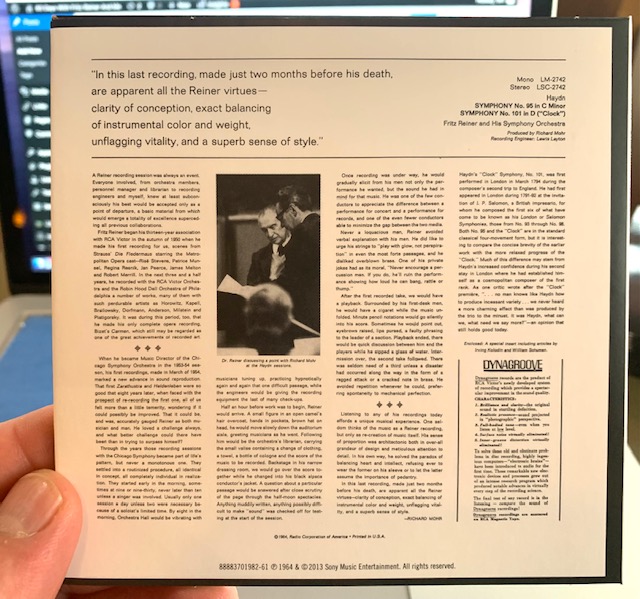

Haydn was 61 0r 62 when he completed his “Clock” Symphony. It was recorded on two days in 1963, tracks 1 and 4 on September 13, and tracks 2 and 3 on September 16. Maestro Reiner was in his 75the year of life, and two months before his death. It was recorded at the Manhattan Center in New York City.

This performance is credited to Fritz Reiner and His Symphony Orchestra, which involved musicians from the four different orchestras: the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, the New York Philharmonic, and the Symphony of the Air (formerly the NBC Orchestra), and others.

NOTE: I wasn’t aware this performance existed, or was recorded. According to the book in CD box set, I thought the last recorded performance with Fritz Reiner was on April 20, 1963, which I wrote about on Day 58 of my project. However, now that I look at the words more closely, it actually reads, “Fritz Reiner’s last recording with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.”

After reading that, my assumption was that Maestro Reiner didn’t record any more after April 20, 1963. I was wrong. He performed/recorded again as late as September 20, 1963 – less than two months before his death on November 15, 1963 – just not with the CSO.

So this album is actually quite historic.

Even the cover notes that Fritz Reiner lived 1888-1963, a credit above the composer’s name (Haydn) and his compositions (Symphony No. 101 in D and Symphony No. 95 in C Minor).

The first, and most noticeable, copy on the back of the album reads,

In this last recording, made just two months before his death, are apparent all of the Reiner virtues – clarity of composition, exact balancing of instrumental color and weight, unflagging vitality, and a superb sense of style.

You know, I think I can agree with every one of those attributes.

And that brings up something I hadn’t considered before regarding conductors: they are responsible for the “balancing of instrumental color and weight.”

From its entry on Wikipedia,

The Symphony No. 95 in C minor (Hoboken I/95) is the third of the twelve London symphonies (numbers 93–104) written by Joseph Haydn. It is the only one of the twelve London symphonies in a minor key, and is also the only one of them to lack a slow introduction.

It was completed in 1791 as one of the set of symphonies composed for his first trip to London. It was first performed at the Hanover Square Rooms in London during the season of 1791; the exact date of the premiere is unknown.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 5 ( both)

Overall musicianship: 5 ( both)

CD booklet notes: 2

CD “album cover” information: 5 (a very nice tribute to Maestro Reiner)

How does this make me feel: 5

Despite the fact that Haydn can be a bit sleepy, and certainly “Clock” has a metronome feel to it, especially in the second movement, I found these two performances to be exceptionally good.

Some of the copy near the end of the essay (written by Richard Mohr) reads,

Listening to any of his recordings today affords a unique musical experience. One seldom thinks of the music as a Reiner recording, but only as a re-creation of music itself. His sense of porportion was architectonic both in over-all grandeur of design and meticulous attention to detail. In his own way, he solved the paradox of balancing heart and intellect, refusing ever to wear the former on his sleeve or to let the latter assume the importance of pedantry.

I thoroughly enjoyed this album, both performances. They were very well recorded and exceptionally well played.

In fact, I don’t think I’ve ever heard Haydn played better.

Yes. I’d listen to this album again.

It is a fitting final word from one of the greatest conductors of all time.