Now this is more like it: Beethoven.

I’m a huge fan of Ludwig’s. In fact, my top three Classical composers are Bruckner, Beethoven, and Mozart – in that order. (Or, maybe Ludwig and Anton are tied for first. I can’t tell. Both offer some of the greatest music I’ve ever heard in my life.)

Whatever. The point is I have a bromance going with the

Two of my former music projects were to listen to nine symphonies from Beethoven and Bruckner, as performed by a dozen or two conductors and orchestras. My goal was to find the “best” box set for both composers.

Here’s how I did it:

63 More Days With Bruckner And Me

162 Days With Beethoven And Me

I enjoyed those explorations so much that I’m thinking of doing it again, only this time with Antonín Dvořák’s symphonies. (Because I was so impressed with the one I heard in this Fritz Reiner box set.) Or even round up a bunch of music from Alan Hovhaness, whom I also fell in love with immediately thanks to this hearing him in this musical exploration of Reiner’s RCA albums.

I mention all that to confess that I’m a huge fan of Beethoven, and literally heard five and a half months of his symphonies performed by 17 of the world’s greatest conductors as compiled in 18 different box sets from some of the world’s very best orchestras.

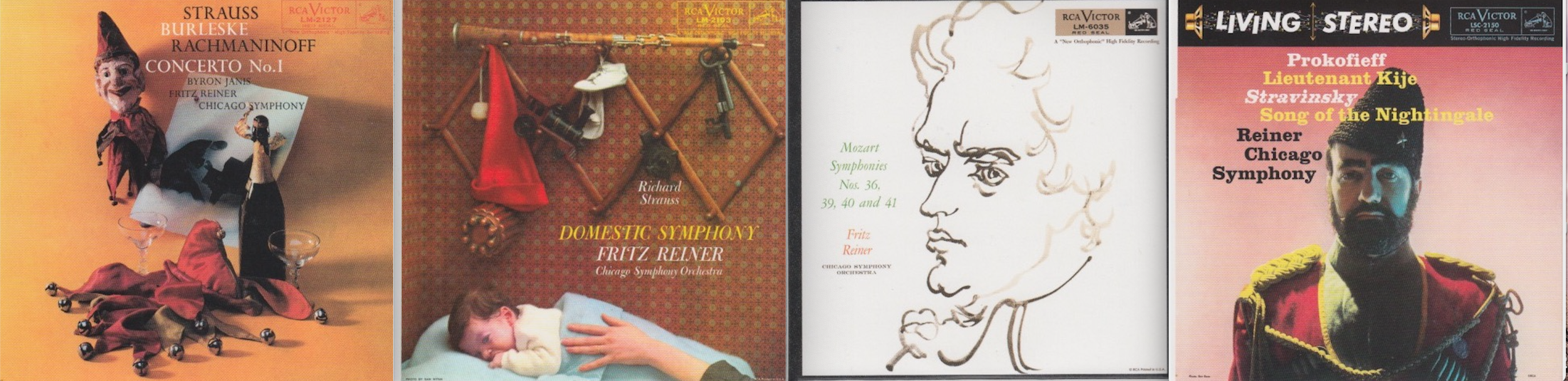

In all of my music explorations of Bruckner and Beethoven – in this case, a total of 369 days (over one solid year of daily listening!), I never once encountered Fritz Reiner. Not once.

So I’m hearing today’s Beethven symphony – from my perch in the restaurant that serves up the Asiago bagels (toasted twice!), Light Roast coffee, and horrible piped-in music – conducted by Maestro Reiner, for the first time.

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) was a German composer and pianist. Beethoven remains one of the most admired composers in the history of Western music; his works rank amongst the most performed of the classical music repertoire, and span the transition from the classical period to the romantic era in classical music. His career has conventionally been divided into early, middle, and late periods. The “early” period, during which he forged his craft, is typically considered to have lasted until 1802. From 1802 to around 1812, his “middle” period showed an individual development from the “classical” styles of Joseph Haydn and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and is sometimes characterized as “heroic”. During this time, he began to suffer increasingly from deafness. In his “late” period from 1812 to his death in 1827, he extended his innovations in musical form and expression.

From its entry on Wikipedia,

The Symphony No. 5 in C minor of Ludwig van Beethoven, Op. 67, was written between 1804 and 1808. It is one of the best-known compositions in classical music and one of the most frequently played symphonies, and it is widely considered one of the cornerstones of western music. First performed in Vienna’s Theater an der Wien in 1808, the work achieved its prodigious reputation soon afterward. E. T. A. Hoffmann described the symphony as “one of the most important works of the time”. As is typical of symphonies during the transition between the Classical and Romantic eras, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is in four movements.

It begins with a distinctive four-note “short-short-short-long” motif…

Indeed. Everybody on the planet knows that “short-short-short-long” motif. It has become synonymous with Classical music.

Wikipedia continues…

The Fifth Symphony had a long development process, as Beethoven worked out the musical ideas for the work. The first “sketches” (rough drafts of melodies and other musical ideas) date from 1804 following the completion of the Third Symphony. Beethoven repeatedly interrupted his work on the Fifth to prepare other compositions, including the first version of Fidelio, the Appassionata piano sonata, the three Razumovsky string quartets, the Violin Concerto, the Fourth Piano Concerto, the Fourth Symphony, and the Mass in C. The final preparation of the Fifth Symphony, which took place in 1807–1808, was carried out in parallel with the Sixth Symphony, which premiered at the same concert.

Beethoven was in his mid-thirties during this time; his personal life was troubled by increasing deafness. In the world at large, the period was marked by the Napoleonic Wars, political turmoil in Austria, and the occupation of Vienna by Napoleon’s troops in 1805. The symphony was written at his lodgings at the Pasqualati House in Vienna. The final movement quotes from a revolutionary song by Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle.

I read somewhere that Beethoven’s deafness may have been caused by lead poisoning. Here’s a very scientific (seemingly medical) analysis of that possibility.

Nobody is sure what caused it, although this web site offers quite a bit of first-hand (from Beethoven’s diaries) testimony.

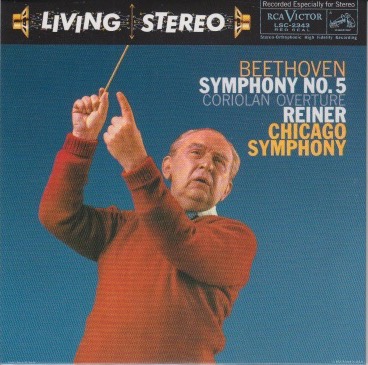

Beethoven’s Fifth was recorded on May 4, 1959, in Orchestra Hall, Chicago. Fritz Reiner was about 71.

Then, there’s the second composition on today’s CD, which – according to its entry on Wikipedia – is,

The Coriolan Overture, Op. 62, is a composition written by Ludwig van Beethoven in 1807 for Heinrich Joseph von Collin’s 1804 tragedy Coriolan.

The structure and themes of the overture follow the play very generally. The main C minor theme represents Coriolanus’ resolve and war-like tendencies (he is about to invade Rome), while the more tender E-flat major theme represents the pleadings of his mother to desist. Coriolanus eventually gives in to tenderness, but since he cannot turn back having led an army of his former enemies to Rome’s gates, he kills himself. (This differs from the better-known play Coriolanus by William Shakespeare, in which he is murdered. Both Shakespeare’s and Collin’s plays are about the same semi-legendary figure, Gaius Marcius Coriolanus, whose actual fate was not recorded.)

The overture was premiered in March 1807 at a private concert in the home of Prince Franz Joseph von Lobkowitz. The Symphony No. 4 in B-flat and the Piano Concerto No. 4 in G were premiered at the same concert.

Coriolan Overture was recorded on May 5, 1959, in Orchestra Hall, Chicgao. Reiner was 71.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 5 (for all compositions)

Overall musicianship: 5

CD booklet notes: 2

CD “album cover” information: 4 (lots of really tiny print)

How does this make me feel: 3 (for Symphony No. 5) / 4 (for Coriolan Overture)

As I wrote earlier, I’ve heard a lot of Beethoven symphonies, conducted by some of the world’s greatest maestros, performed by some of the world’s greatest orchestras, spanning more than a half century of performances. So I have a feel for this piece of music.

Although my opinion will not be popular, something feels off about this performance of Beethoven’s Fifth. I don’t know if the tempi is quicker than usual, or if some indefinable element of power is missing. But it lacks oomph.

And the third movement (Scherzo – Allegro), which is the one that really gripped me when I first heard it several years ago, failed to do so this time.

I remember when I got to Movement III the first time I heard it, I stopped dead in my tracks. It was unexpected, and incredibly gorgeous. I was moved. I had to share it with my wife later that night.

This time around, with Fritz Reiner and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, I didn’t feel the Wow Factor. I remember the feeling I had before. And I felt badly that I didn’t have it this time.

Again, this is a masterfully competent performance. It is rock solid. Anyone else listening to it, might hear absolutely perfection…and then proceed to ridicule me for not hearing that same perfection.

It’s not that I don’t hear the perfection. It’s that I’m not hearing the emotion, the power…the magic. The pizzicato of Movement III gives me a grin or two. But it doesn’t convince me that this is a performance that stands above all others.

As for the Coriolan Overture, I found it to be slightly more appealing to me, possibly because I don’t remember hearing it before, so I had nothing by which to compare it. I enjoyed its big, bold performance, which was lushly recorded.

Overall, I liked this album. I just didn’t love it, and I see no reason to ever hear this particular performance again.