Here’s another example of what appears to be a misspelling on the album cover.

On Day 24, I had to look up the word “pavan” as it was used in the liner notes on the back of the album. Turns out, there’s no such word. It was supposed to be “parvane,” which is – according to its entry on Wikipedia – “a slow processional dance common in Europe during the 16th century (Renaissance).”

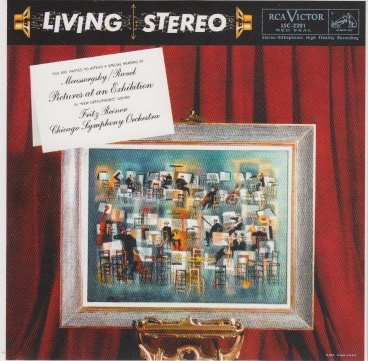

Okay. So I come to today’s album, listed as “Moussorgsky.”

And yet his name is Mussorgsky (no “u” as in “m-o-u-s-e”).

So where did “Moussorgsky” come from?

I’m going to use the Wikipedia (and commonly held) spelling “Mussorgsky” from now on.

Whenever I hear Mussorgsky’s Pictures At An Exhibition, I immediately think of the legendary Progressive Rock band Emerson Lake & Palmer and their full-length concert version of it.

A link to ELP’s version is below.

A word to the wise, however. Some ass clown producer or director decided to add a bunch of trippy, psychedelic graphics in key moments of the concert film.

The end result is legions of pissed-off fans today who just wanted to see some of the 20th century’s most accomplished musicians, at the top of their game, play their instruments.

Alas.

There are rumors that the Japanese LaserDisc (and subsequent DVD transfer) of this concert omits the trippy graphics. But, so far, I haven’t been able to verify that one way or another.

So, if you watch the YouTube video below, and you feel yourself getting nauseated from the LSD-inspired graphics, don’t blame me.

Okay.

I’ll save you the headache.

Here’s that same music without the visuals.

This is how I remember Pictures At An Exhibition – as performed by ELP.

Frankly, I still prefer ELP’s version to the one by Fritz Reiner and CSO.

But I’ll save that for the next section…

The Objective Stuff

From his entry on Wikipedia,

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky (1839 – 1881) was a Russian composer, one of the group known as “The Five”. He was an innovator of Russian music in the Romantic period. He strove to achieve a uniquely Russian musical identity, often in deliberate defiance of the established conventions of Western music.

Many of his works were inspired by Russian history, Russian folklore, and other national themes. Such works include the opera Boris Godunov, the orchestral tone poem Night on Bald Mountain and the piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition.

For many years, Mussorgsky’s works were mainly known in versions revised or completed by other composers. Many of his most important compositions have posthumously come into their own in their original forms, and some of the original scores are now also available.

Contemporary opinions of Mussorgsky as a composer and person varied from positive to ambiguous to negative. Mussorgsky’s eventual supporters, Vladimir Stasov and Mily Balakirev, initially registered strongly negative impressions of the composer. Stasov wrote Balakirev, in an 1863 letter, “I have no use for Mussorgsky. His views may tally with mine, but I have never heard him express an intelligent idea. All in him is flabby, dull. He is, it seems to me, a thorough idiot”, and Balakirev agreed: “Yes, Mussorgsky is little short of an idiot.”

Mixed impressions are recorded by Rimsky-Korsakov and Tchaikovsky, colleagues of Mussorgsky who, unlike him, made their living as composers. Both praised his talent while expressing disappointment with his technique. Rimsky-Korsakov wrote that Mussorgsky’s scores included

absurd, disconnected harmony, ugly part-writing, sometimes strikingly illogical modulation, sometimes a depressing lack of it, unsuccessful scoring of orchestral things… what was needed at the moment was an edition for performance, for practical artistic aims, for familiarization with his enormous talent, not for the study of his personality and artistic transgressions.

While preparing an edition of Sorochintsï Fair, Anatoly Lyadov remarked: “It is easy enough to correct Mussorgsky’s irregularities. The only trouble is that when this is done, the character and originality of the music are done away with, and the composer’s individuality vanishes.”

From its entry on Wikipedia,

Pictures at an Exhibition is a suite of ten pieces—plus a recurring, varied Promenade—composed for piano by Russian composer Modest Mussorgsky in 1874.

The suite is Mussorgsky’s most famous piano composition, and has become a showpiece for virtuoso pianists. It has become further known through various orchestrations and arrangements produced by other musicians and composers, with Maurice Ravel’s 1922 version for full symphony orchestra being by far the most recorded and performed.

The composition is based on pictures by the artist, architect, and designer Viktor Hartmann. It was probably in 1868 that Mussorgsky first met Hartmann, not long after the latter’s return to Russia from abroad. Both men were devoted to the cause of an intrinsically Russian art and quickly became friends. They likely met in the home of the influential critic Vladimir Stasov, who followed both of their careers with interest. According to Stasov’s testimony, in 1868, Hartmann gave Mussorgsky two of the pictures that later formed the basis of Pictures at an Exhibition. In 1870, Mussorgsky dedicated the second song (“In the Corner”) of the cycle The Nursery to Hartmann. Stasov remarked that Hartmann loved Mussorgsky’s compositions, and particularly liked the “Scene by the Fountain” in his opera Boris Godunov. Mussorgsky had abandoned the scene in his original 1869 version, but at the requests of Stasov and Hartmann, he reworked it for Act 3 in his revision of 1872.

Hartmann’s sudden death on 4 August 1873 from an aneurysm shook Mussorgsky along with others in Russia’s art world. The loss of the artist, aged only 39, plunged the composer into deep despair. Stasov helped to organize a memorial exhibition of over 400 Hartmann works in the Imperial Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg in February and March 1874. Mussorgsky lent to the exhibition the two pictures Hartmann had given him, and viewed the show in person. Later in June, two-thirds of the way through composing his song cycle Sunless, Mussorgsky was inspired to compose Pictures at an Exhibition, quickly completing the score in three weeks (2–22 June 1874). In a letter to Stasov (see photo), probably written on 12 June 1874, he describes his progress:

The music depicts his tour of the exhibition, with each of the ten numbers of the suite serving as a musical illustration of an individual work by Hartmann.

Interesting.

Mussorgsky was 35 when he composed this suite with 10 pieces. It was recorded on December 7, 1957, in Orchestra Hall, Chicago. Reiner was about 69 when he conducted the CSO for this performance. Just for the record, the story of Mussorgsky’s decline and death (likely due to alcoholism) at the age of 42 is a depressing read.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 5

Overall musicianship: 5

CD booklet notes: 2

CD “album cover” information: 4.5

How does this make me feel: 5

In spite of Mussorgsky’s depressing life, I found this to be a remarkable performance.

To my ears, it was recorded brilliantly – full of depth, clarity, and vitality – and performed with more than the typical Reiner precision.

I think the quality of the recording is most evident on movements like “Ballet of the Chicks in Their Shells.” All of the instruments are crystal clear, and played with wit and verve.

It was like these musicians were inspired.

I thought Mussorgky’s idea for a suite (music composed for a series of paintings) was quite good, and I found several of these movements rather engaging, to wit:

- The opening to the first movement – Promenade, which becomes a recurring theme throughout the composition and features (in its second appearance) French horns…and an increasing energy and grandness

- The fourth movement – Il vecchio castello (The Old Castle, the Second Picture) – which is an extremely compelling piece of music; all lyrical and mysterious

- The ninth movement – Ballet of the Chicks in Their Shells (the Fifth Picture) – which is appropriately comical and lively

- The final movement – The Great Gate at Kiev (the tenth Picture) – which is as bombastic a piece of music as ELP ever envisioned.

Maybe when I hear this, I hear ELP, especially the haunting opening and recurring theme, Promenade. Maybe I hear Greg Lake’s voice. Maybe I hear ELP’s explosive ending, The Great Gate at Kiev.

Or maybe Mussorgsky’s composition truly was brilliant, despite what some of his friends and contemporary composers thought of him.

I don’t know why this music appeals to me. It just does.

I’d listen to this album again (and I’ve already heard it through four times). So that must mean something, right?