I cannot even begin to tell you how much I dislike the opening to Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto No. 1.

Whenever I hear it, I immediately think of hokey music sold on TV, or played – in an appropriately flamboyant manner, with exaggerated hand movements and the use of way too many notes – by third-rate lounge acts.

Frankly, this is how I’ve always viewed Tchaikovsky – as the Yngwie Malmsteen of Classical music. Malmsteen, a Swedish heavy metal guitarist whose style is often classified as “neoclassical,” is known for playing a flurry of notes as quickly and as often as possible.

Don’t take my word for it. Judge for yourself:

Malmsteen is one of the world’s greatest guitarists. No doubt about that. (Just ask him. He’ll corroborate it.) I cannot deny he has talent.

Yet, few guitarists deserve the title “showboat” more than Yngwie Malmsteen.

As I’m listening to today’s music from Tchaikovsky, I cannot help but think of Malmsteen, and wonder “Why did Pyotr feel he had to play so many damn notes?”

First, I’ll take a look at his life. Maybe there’s an answer to be found there.

From the Wikipedia entry about Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)) was a Russian composer of the Romantic period. He was the first Russian composer whose music would make a lasting impression internationally. He was honored in 1884 by Tsar Alexander III and awarded a lifetime pension.

Although musically precocious, Tchaikovsky was educated for a career as a civil servant. There was scant opportunity for a musical career in Russia at the time and no system of public music education. When an opportunity for such an education arose, he entered the nascent Saint Petersburg Conservatory, from which he graduated in 1865. The formal Western-oriented teaching that he received there set him apart from composers of the contemporary nationalist movement embodied by the Russian composers of The Five with whom his professional relationship was mixed.

Tchaikovsky’s training set him on a path to reconcile what he had learned with the native musical practices to which he had been exposed from childhood. From that reconciliation, he forged a personal but unmistakably Russian style.

Two things about the above stood out to me:

- He was only 53 when he died (and, according to Wiki, no one knows how or why), and

- The Romantic period. I haven’t listened to much music from the Romantic period, which according to Wikipedia,

was an artistic, literary, musical, and intellectual movement that originated in Europe towards the end of the 18th century, and in most areas was at its peak in the approximate period from 1800 to 1850. Romanticism was characterized by its emphasis on emotion and individualism as well as glorification of all the past and nature, preferring the medieval rather than the classical. It was partly a reaction to the Industrial Revolution, the aristocratic social and political norms of the Age of Enlightenment, and the scientific rationalization of nature—all components of modernity. It was embodied most strongly in the visual arts, music, and literature, but had a major impact on historiography, education, chess, social sciences, and the natural sciences. It had a significant and complex effect on politics, with romantic thinkers influencing liberalism, radicalism, conservatism, and nationalism.

The movement emphasized intense emotion as an authentic source of aesthetic experience, placing new emphasis on such emotions as fear, horror and terror, and awe — especially that experienced in confronting the new aesthetic categories of the sublime and beauty of nature.

Most of the Classical music to which I listen ended with Beethoven (who died in 1827), with the notable exception of Anton Bruckner (1824-1896), who lived during the Romantic period but who deftly combined the Classical period with the Romantic so that his Classical works were steeped in emotion and spirituality.

Musicologists and historians (both of which I am not) might differ with my opinion. But I’ve listened to months and months of Bruckner’s music, and I can attest that it moves me deeply on emotional and spiritual levels. So I know Anton was tapping into something from the Romantic period, even if his compositions were quite traditional in their execution.

Okay, back to showboat Tchaikovsky.

Even when these compositions use one of my favorite techniques (pizzicato, which always puts a smile on my face because it reminds me of one cartoon character tip toeing to sneak up on another one), and even when the orchestra sounds lush and grand, I cannot get past the feeling that Tchaikovsky is a showboat.

The first movement, for example, starts with that horrendous music often played by hacks to entertain the old folks in nightclubs and in donut shops, and then it runs the gamut of moods and tempos.

To me, Tchaikovsky wrote to showcase himself, rather than to create a composition that showcased itself.

Too many damn notes!

Who’s playing the piano in this performance? A musician named Emil Gilels (1916-1985), who – according to his entry on Wikipedia,

…was a Soviet pianist. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest pianists of all time.

Gilels is universally admired for his superb technical control and burnished tone. Gilels had a repertoire ranging from baroque to late Romantic and 20th century classical composers. His interpretations of the central German-Austrian classics formed the core of his repertoire, in particular Beethoven, Brahms, and Schumann; but he was equally illuminative with Scarlatti and 20th-century composers such as Debussy, Rachmaninoff, and Prokofiev. His recordings of Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 9 and Sonata in B minor have acquired classic status in some circles.

Gilels was one of the first Soviet artists, along with David Oistrakh, allowed to travel and give concerts in the West. His American debut was in October 1955, with the Philadelphia Orchestra and Eugene Ormandy. His British debut was in 1952 at the Royal Albert Hall. Gilels made his Salzburg Festival debut in 1969 with a piano recital of Weber, Prokofiev and Beethoven at the Mozarteum, followed by a performance of Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto with George Szell and the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra.

In 1981, Gilels suffered a heart attack after a recital at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam and suffered declining health thereafter. He died unexpectedly during a medical checkup in Moscow on 14 October 1985, only a few days before his 69th birthday. Sviatoslav Richter, who knew Gilels well and was a fellow-student in the class of Heinrich Neuhaus at the Moscow Conservatory, believed that Gilels was killed accidentally when a drug was wrongly injected during a routine checkup, at the Kremlin hospital. However, Danish composer and writer Karl Aage Rasmussen, in his biography of Richter, denies this possibility and contends that it was just a false rumour.

There’s no doubt Gilels was a masterful player. It takes an enormous about of talent to play Tchaikovsky’s music well.

But, for the same reason why I don’t listen to a lot of Malmsteen, I don’t listen to a lot of Tchaikovsky – in fact, none. I prefer more rest for my mind, more space between notes.

A good example: The second movement (Andantino semplice – Prestissimo – Tempo I) features some beautiful music in it. But then (like around the 3:34 mark), a flurry of notes appears and – quicker than you can say “Bob’s your uncle” (I’ve always wanted to use that phrase) – I’ve been Malmsteened! I’m immediately yanked out of my reverie.

After the flurry of notes, that movement sounds like a mash-up of Rimsky-Korsakov’s (what’s with these Russians, anyway? Did they get paid by the note?) The Flight of the Bumblebee and demented circus music. After the crazed circus music, the movement returns to a reverie and I float on clouds to the pizzicato end.

The third movement (Allegro con fuoco) begins with both reverie and a Malmsteen-like flurry of notes. And then what sounds like a can-can interlude cuts in (Offenbach would be proud), along with more note flurries.

I just thought of something else Tchaikovsky reminds me of: the late Keith Emerson, one third of the famed Prog Rock band ELP (Emerson Lake & Palmer). Their triple live album (titled Welcome Back, My Friends, to the Show That Never Ends – Ladies and Gentlemen) was released in 1974. I bought it. Loved it. But I remember the review from either Circus or Creem magazine was short. Something like “Everything but the kitchen sink.”

Anyway, Keith Emerson, a gifted and superb pianist, would occasionally burst into a thousand-note flurry…but then back off, slow it down…then ramp up in showboat fashion…then back off. Emerson knew that if all he gave the audience was a performance always on “11” (to borrow Nigel Tufnel’s now-famous phrase), they’d never really know how good he was. They’d tire of his prowess and, eventually, take it for granted.

Tchaikovsky is almost always turned up to 11.

And I’m tired of his prowess. (See how that works?)

The Objective Stuff

This was recorded on October 29, 1955, at Orchestra Hall. Pianist Emil Gilels was 39. Conductor Reiner was 67. Tchaikovsky was 34 or 35 when he composed it in 1874 – 1875.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 3

Overall musicianship: 5 (for Emil Gilels, alone)

CD booklet notes: 2

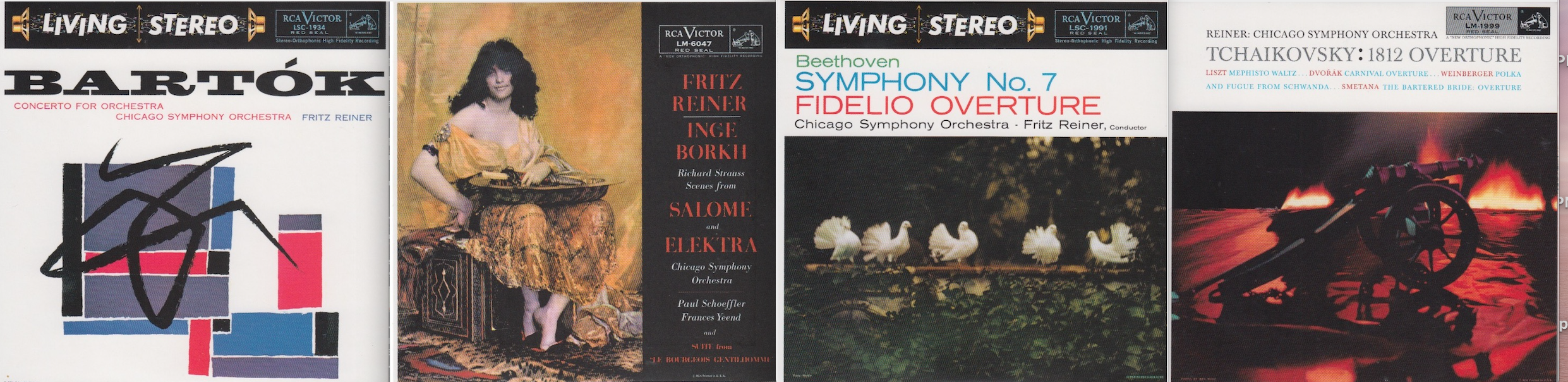

CD “album cover” information: 5

How does this make me feel: 1

I could probably live the rest of my life without hearing this album again.

And I’d be okay with that.