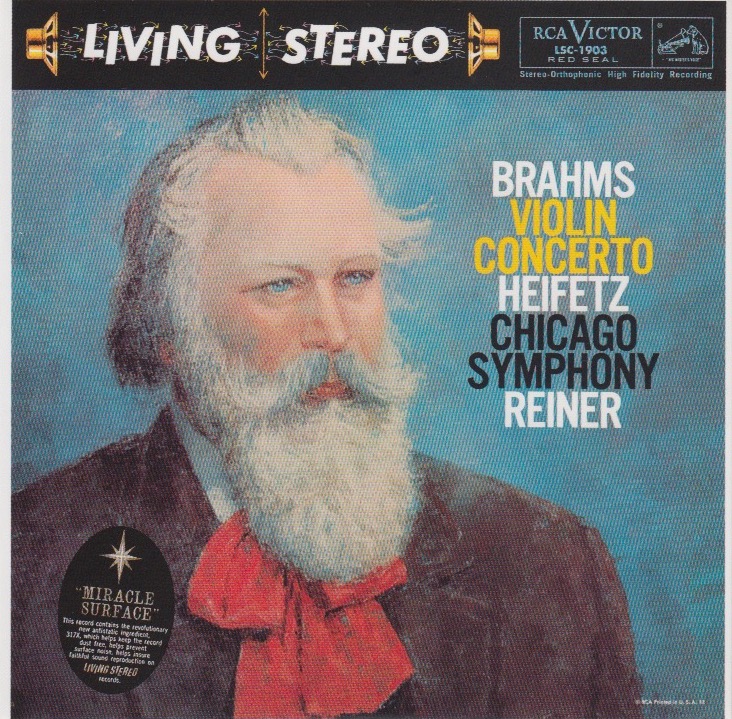

This morning, I return to Brahms, one of my least favorite Classical composers (second only to Haydn as composers I just didn’t get), although this time I am treated to the debut (to my ears, anyway) of Jascha Heifetz, widely regarded as one of the world’s greatest violinists.

From his entry on Wikipedia:

Jascha Heifetz (1901-1987) was a Russian-American violinist. Born in Vilna (Vilnius), he moved as a teenager to the United States, where his Carnegie Hall debut was rapturously received. He was a virtuoso since childhood—Fritz Kreisler, another leading violinist of the twentieth century, said on hearing Heifetz’s debut, “We might as well take our fiddles and break them across our knees.” He had a long and successful performing career. However, after an injury to his right (bowing) arm, he switched his focus to teaching.

Heifetz was “regarded as the greatest violin virtuoso since Paganini”, wrote Lois Timnick of the Los Angeles Times. “He set all standards for 20th-century violin playing…everything about him conspired to create a sense of awe”, wrote music critic Harold Schonberg of The New York Times.”The goals he set still remain, and for violinists today it’s rather depressing that they may never really be attained again”, wrote violinist Itzhak Perlman.

Virgil Thomson called Heifetz’s style of playing “silk underwear music”, a term he did not intend as a compliment. Other critics argue that he infused his playing with feeling and reverence for the composer’s intentions. His style of playing was highly influential in defining the way modern violinists approached the instrument. His use of rapid vibrato, emotionally charged portamento, fast tempi, and superb bow control coalesced to create a highly distinctive sound that makes Heifetz’s playing instantly recognizable to aficionados. Itzhak Perlman, who himself is known for his rich warm tone and expressive use of portamento, described Heifetz’s tone as like “a tornado” because of its emotional intensity. Perlman said that Heifetz preferred to record relatively close to the microphone—and as a result, one would perceive a somewhat different tone quality when listening to Heifetz during a concert hall performance.

Heifetz was very particular about his choice of strings. He used a silver wound Tricolore gut G string, plain unvarnished gut D and A strings, and a Goldbrokat medium steel E string, and employed clear Hill-brand rosin sparingly. Heifetz believed that playing on gut strings was important in rendering an individual sound.

Even though I’d heard the name Heifetz many times over the past couple of decades, I couldn’t say for sure if I’d ever heard the man play. Now I can say that I have.

I’m back in one of my unofficial offices – the one with the Asiago bagels (toasted twice), the Light Roast coffee (when the urn is kept filled), and the god-awful music piped in to torment its patrons.

Thankfully, I have on my headphones, so my ears aren’t bleeding from the sonic assault, even as my tummy is placated by the bagel and coffee.

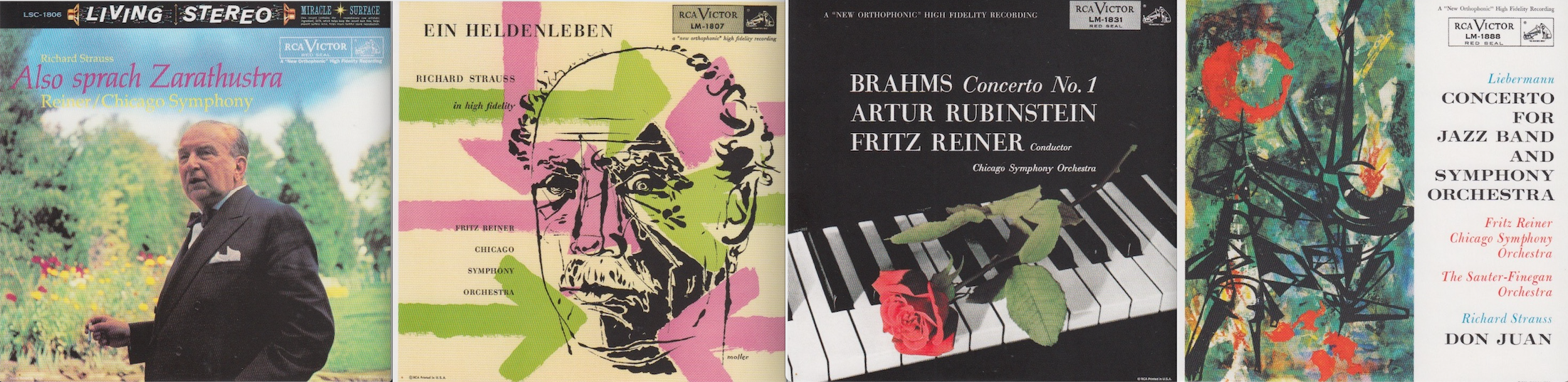

Three things stood out on this morning’s album covers, front and back:

- The mention of “Miracle Surface” on the front. “Miracle Surface” was supposedly “the revolutionary new antistatic ingredient 317X, which helps keep the record dust free, helps prevent surface noise, helps insure faithful sound reproduction on LIVING STEREO records.”

- The IMPORTANT NOTICE on the back cover alerting me that “This is a TRUE STEREOPHONIC RECORD specifically designed to be played only on phonographs equipped for stereophonic reproduction.” Good to know.

- The article/review on the back of the album is not only visible to my unaided eyes, it was written by someone I had to look up to discover who she was: Claudia Cassidy (1899-1996).

It is to point #3 that I turn now. According to her entry on Wikipedia, Claudia Cassidy was a force to be reckoned with:

Claudia Cassidy (1899–1996), was an influential, 20th-century American performing arts critic. She was a long-time critic for the Chicago Tribune.

Starting in 1925 she was music and drama critic for The Journal of Commerce. She was so well known for giving caustic reviews to what she considered bad performances that she earned the nickname “Acidy Cassidy.”According to a 1993 article by the Chicago Reader, Rafael Kubelik, was “practically hounded out of town” by Cassidy.[3] Cassidy had a particular aversion to touring companies of Broadway shows.

Although she was known for her harsh criticism, Cassidy’s enthusiasm may have been even more powerful.

Cassidy was married to William J. Cassidy for 57 years. After her husband died in 1986, Cassidy lived at the Drake Hotel until her death in 1996 at the age of 96.

Now, see, if it hadn’t been for the fact that the article/review on the back of the album being legible, if not for my scrutiny (with my iPhone) of some of the smaller print, the name “Claudia Cassidy” would not have jumped out at me. As it was, I learned more this morning than I bargained for. Call it a bonus, if you wish. I do.

As for the recording, it is sublime.

Violin Concert in D, Op. 77, was composed by Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) in 1897. From its entry on Wikipedia,

The Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 77, was composed by Johannes Brahms in 1878 and dedicated to his friend, the violinist Joseph Joachim. It is Brahms’s only violin concerto, and, according to Joachim, one of the four great German violin concerti:

The Germans have four violin concertos. The greatest, most uncompromising is Beethoven’s. The one by Brahms vies with it in seriousness. The richest, the most seductive, was written by Max Bruch. But the most inward, the heart’s jewel, is Mendelssohn’s.

Of course, you know what that means, don’t you?

The gauntlet has been laid down. Now I have to acquire all four of those violin concerti. I have Beethoven’s. Obviously, I have Brahms’ I don’t even know who Max Bruch is. But whenever someone writes “remastered” or “limited edition” or “the greatest,” I spring into action like Commissioner Gordon had just throw up the Bat Signal.

Rest assured, I’ll have ordered the two (Bruch and Mendelssohn) before I’m finished with this blog entry.

Back to said blog entry.

The Objective Stuff

This was recorded over two days (February 21 & 22) in 1955. Where? I don’t know. The CD book notes don’t indicate where, although the Kenneth Morgan book mentions the “hall,” so I assume it’s the Orchestra Hall – although I shouldn’t have to assume anything. That information should have been in the CD book notes. Heifetz was 54 when this was recorded. Brahms was 45 when he composed it. Reiner was 67 when he conducted it.

The Subjective Stuff

Recording quality: 5

Overall musicianship: 5

CD booklet notes: 2

CD “album cover” information: 5

How does this make me feel: 5

One of the ways I judge “how does this make me feel” is by how many times I listen to it, how much I research because of it, and how engaged I am with the performance. Oh, and the quality of the recording. That goes without saying.

Heifetz elevates this performance the way Rubinstein elevated the Brahms Concerto No. 1 performance on Day 3.

Overall, I’d give this a 5 no matter what because of the power of Jascha Heifetz’s performance. I was moved.

Oh, one more thing. Kenneth Morgan writes about this recording session on page 194 of his book Fritz Reiner Maestro & Martinet. He writes that it was a troublesome session that rant too long and involved too many attempts at “improvements,” when the first take (played straight through) was likely the best one. Reiner, according to Morgan, was known to tinker with the recordings, sometimes missing out on the spontaneity of the first one, which was often the best. It’s a long paragraph worth reading. Buy his book.